¿Cómo ha afectado la pandemia a la comunidad del sur de Asia en el Reino Unido?

Back in June 2020, research published by the University of Edinburgh found that south Asians are more likely to die from Coronavirus, than any other ethnicity.

The study on different ethnicities and their outcomes observed a cohort of 35,000 patients in 260 hospitals across England, Scotland and Wales, from February to May 2020, and found that, after being admitted to hospital for Covid19, the ethnic group were 20% more likely to die than white people. In particular, people of Bangladeshi ethnicity had around twice the risk of death than people of White British ethnicity. Furthermore, in an Office of National Statistics analysis of death certificates where Coronavirus was mentioned, from April to May 2020, it was found that Bangladeshi and Pakistani men were 1.8 times more likely to have a COVID-19-related death than white men. For women the figure was 1.6 times more likely.

With something like a global pandemic, it’s hard to compare how it has effected one group of people over another. After all, all around the world people have suffered from the virus and all around the world people have died from it. But as these statistics prove, in the UK, as in many other western countries, ethnic minorities have seen some of the highest infection and death rates. But it’s not entirely clear why.

A las mujeres violadas en Reino Unido les aconsejan que se suiciden Kristen Stewart y Charlize Theron en la presentación de Blancanieves y la Leyenda del Cazador en el Reino Unido

This heightened risk of death for south Asians, found by the University of Edinburgh was thought to be partly because of the higher incidence of diabetes: south Asians are six times more likely than Europeans to develop type 2 diabetes. And research in conjunction between Diabetes UK and the University of Glasgow found that some contributing factors to this increased risk of diabetes could be a slower rate of fat metabolism, a culturally rich diet and typically low levels of exercise. And unfortunately, diabetes both increases the risk of infection and damages the body’s organs, making it harder to survive the Coronavirus.

However a number of other studies have identified other factors that could be contributing to the higher covid-related statistics found in the British south Asian communities. OpenSafely, a secure analytics platform for electronic health records in the NHS, created to deliver urgent results during the pandemic, facilitated a study between the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the University of Oxford, TPP - a healthcare software company and the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC).

This collaboration looked at the factors associated with COVID-19-related hospital deaths in the linked electronic health records of 17 million adult NHS patients and found that those living in the most deprived areas are at around double the risk of death compared to those from the least deprived areas. UK government data collection in 2019, saw that most ethnic minority groups were more likely than White British people to live in the most overall deprived 10% of neighbourhoods in England.

There has also been a higher prevalence of cases in densely populated urban areas like London and Birmingham, both of which have large south Asian populations. In London, for example, the second largest ethnicity is Asian at 18.5%. South Asians also typically live in large, mixed and intergenerational households, where school children who can be easy carriers co-exist with elderly, and therefore vulnerable, members of the family.

Huge numbers of BAME individuals also work as frontline staff in the health sector and as key workers working in transport and delivery, as taxi drivers and as security guards and are therefore more exposed to the virus. Migrant individuals may also struggle to have access to healthcare.

But, OpenSafely, also found that adjusting for cardiometabolic factors like diabetes, socioeconomic considerations like home type and overcrowding and behavioural factors like smoking had little effect on the results. This means that the higher risk of death from Covid19, in south Asians is only partially explained by factors like the individual’s environment and pre-existing health conditions. The remaining part of the difference has not yet been explained.

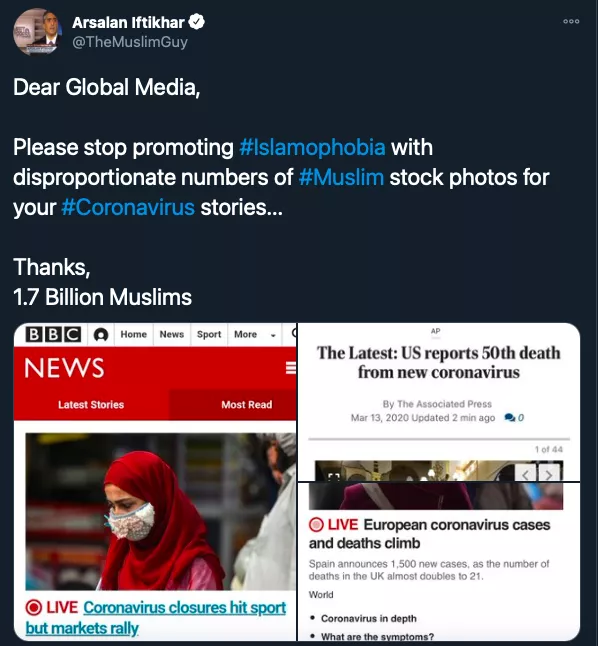

Beyond health, the pandemic has resulted, perhaps unsurprisingly, in a rise in xenophobia and racism towards south Asians. This was particularly true in the summer of 2020 when certain parts of the north were put into lockdown just before Eid. Many south Asians and Muslims in particular suffered verbal racist attacks and slurs after being scapegoated for the rise in cases.

In fact on August 22nd of last year, which is the International Day Commemorating the Victims of Violence Based on Religious Belief, UN Secretary-General António Guterres said, that the pandemic has been accompanied by “a surge in stigma and racist discourse vilifying communities, spreading vile stereotypes and assigning blame.” There have also been cases of subconscious bias in the media, where images of Muslims and mosques have been used in articles about Coronavirus, further perpetuating negative stereotypes.

One area of work that is markedly unique for south Asians and that has seen significant changes this year is the south Asian wedding industry in the UK. South Asians around the world are known to have large, loud and long festivities to celebrate weddings and often, many are expensive and elaborate affairs. But this year, more south Asian couples have chosen to postpone their weddings rather than cancel them altogether.

Having been a wedding planner for twenty years now, Jyoti has noticed that before, it was almost always the parents of the couple who paid for the wedding but now she says, the spending power is with the couples themselves who have saved up a lot for their big day. “It’s heartbreaking,” she dice. “Most south Asian weddings don’t have an RSVP and today it’s realmente difícil de contar para los miembros extendidos de la familia y los ancianos en particular. Para las bodas más grandes, cobran por los números, así que esta incertidumbre puede agregar más presión sobre las parejas.”

Pero ella señala, “algunos proveedores individuales y comerciantes únicos están sobreviviendo en esto, y si las parejas comienzan a cancelar esto, entonces ellos sufren enormemente. Es una industria muy oscura en este momento; le ha puesto una cortina a la gente y muchos han tenido que volver a formarse.”

“En el futuro, puedo ver matrimonios más pequeños”, dice. “Creo que son los padres los que dicen que no invitaron a tal y cual y Covid le dio a las parejas el coraje para decir no queremos algo pequeño para que podamos ahorrar para cosas como una casa y luna de miel pero la gran boda extravagante no cambiará hasta que la próxima generación se convierta en padres.”

Communicating clearly, like Jyoti does, is especially necessary during the pandemic for the south Asian community which is considered one of the ‘hard to reach’ groups by the government. Misinformation has been rampant, especially over Whatsapp, about the way the virus spreads, the severity of the infection and the necessity of precautions like wearing a mask to cover both the nose and mouth, and not just the mouth. In particular, there has been significant misinformation and lack of understanding over the vaccine and how it works.

Dinesh Sejpal, is an elderly, deaf south Asian man who has experienced some of the worst misinformation. “I worry about the Coronavirus vaccine because it might have meat in it,” he says. “I didn’t have much information and spoke to people about it and then I saw on BBC with an interpreter, news about the vaccine but it wasn’t enough information and I wanted more so I can be more clear.”

As was the case for everyone, festivals were deeply affected too. Diwali, for example, was markedly diferente. For 27-year old Londoner Saahil Lakhani “it was strange because normally we would go to my aunt’s and have a massive puja which she would lead followed by a large meal and there would be 25 to 30 of us. This year we did a zoom call, and she showed the puja online. She still made the full dinner, we just all went round and picked it up and ate it at home in our own time so [the celebration] really only lasted about half an hour.”

“When we wanted to close many people asked us if we’re sure because they thought it was fake. But I said if it’s fake, why would the government ask everything to close? We have to follow the rules and regulations and then after one week when people started to see the news and see that people were dying they realised that we have to take it seriously.”